The recent Supreme Court directive to relocate 100% of stray dogs from the Delhi NCR is a decision made with the best intentions—to protect human life. But history, both ancient and recent, is replete with cautionary tales about the unintended consequences of drastically altering an ecosystem. The Black Death, a plague that devastated Europe in the 14th century, offers a grim lesson on how a seemingly logical action can lead to a catastrophic outcome.

It is a widely circulated belief that a mass killing of cats, fueled by superstition and their association with witchcraft, led to a population explosion of rats, which were the primary carriers of the plague. While this narrative is a compelling warning about ecological disruption, historical research suggests the connection is more complex. While some papal decrees in the 13th century did condemn cats, particularly black cats, there is no definitive historical evidence of a widespread, sustained cat-killing spree across Europe that directly caused the plague. Regardless of the historical specifics, the story serves as a powerful metaphor for a simple truth: removing a species from its environment without understanding its ecological role can be disastrous.

Rabies: A Threat Beyond Dogs

The focus of the Supreme Court’s order is on preventing dog bites and the spread of rabies. However, focusing solely on dogs may be a dangerous oversimplification. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), dogs are the primary vector for human rabies in India, responsible for up to 97% of cases. However, other animals can also carry and transmit the virus.

If the entire stray dog population of Delhi were to be removed, it could trigger a “vacuum effect.” Other species, such as rats and monkeys, might see a population boom due to the absence of a natural deterrent. This could lead to a new set of public health crises, including a potential increase in rabies infections from these other animals, a problem far more complex and difficult to manage than the current one. The removal of dogs could upset the delicate urban ecological balance, potentially paving the way for a resurgence of pests and other zoonotic diseases.

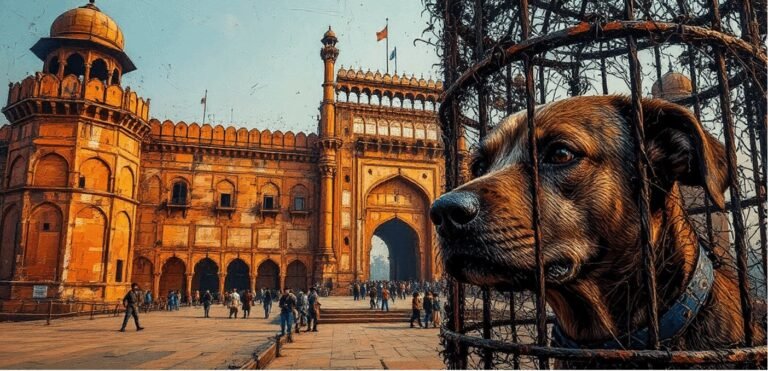

The Ecological Role of Dogs: Guardians of Our Urban Spaces

Far from being a menace, stray dogs are an integral, though often unseen, part of the urban ecosystem. Their presence serves as a form of natural pest control, helping to keep the populations of smaller animals like rats and rodents in check. In doing so, they indirectly mitigate the spread of diseases carried by these pests. They also act as sentinels of their territory, their barks and presence often deterring unfamiliar people or other, more dangerous wildlife from entering a neighborhood. This is a subtle yet vital role they play in society, often providing an unacknowledged sense of security.

A dog’s territorial nature, often perceived as a problem, is actually a built-in mechanism for maintaining a stable environment. A settled, sterilized, and vaccinated dog population in a given locality is a far safer and more manageable scenario than a constant influx of new, unvaccinated dogs fighting for a newly vacated territory. This is why the Animal Birth Control (ABC) program—when properly implemented—is so effective. It respects the dogs’ role in the ecosystem while humanely and scientifically controlling their population and health.

An Ancient Alliance: How Dogs Saved Humanity

The relationship between humans and canines dates back tens of thousands of years to a period when a remarkable alliance formed. As per numerous studies, wolves, the ancestors of modern dogs, began to form a bond with early humans . This alliance wasn’t just a matter of companionship; it was a pact for survival that helped shape the course of human history.

This symbiotic relationship was a game-changer for both species. Early humans benefited immensely from the wolves’ superior hunting skills, keen senses, and ability to track prey. This collaboration made hunting more successful, providing a more stable food supply and allowing early human populations to thrive. In return, the wolves gained a reliable source of food from hunting scraps and the protection of the human group. This partnership is widely credited with helping early human societies survive the challenges of the Ice Age and expand across continents. The domestication of wolves, which eventually led to the dogs we know today, laid the foundation for a shared history of coexistence and mutual benefit.

Inadvertent Repercussions: The Unseen Costs

As detailed in the previous blog, the directive to relocate over a lakh of dogs is a logistical and financial nightmare. The costs of land, feeding, and veterinary care would run into hundreds of crores, diverting public funds from essential services. But beyond the monetary cost, there are the unseen human costs: the anxiety caused by an increase in rat and monkey populations, the emotional toll on a community that loses its animal “guardians,” and the potential for a new public health crisis. It is a sobering example of how a well-intentioned policy, when divorced from ecological and social realities, can inadvertently cause more harm than good. The solution lies not in conflict with nature, but in a well-managed coexistence.